12th Century

Queen Matilda’s Foundation

St Katharine’s was founded in 1147 by Queen Matilda, the wife of King Stephen. In her Charter, Matilda described the Foundation as, “My hospital next to the Tower of London”. She placed it in the custody of the Priory of the Holy Trinity at Aldgate, saying that they were to “maintain in the said Hospital in perpetuity 13 poor persons for the salvation of the soul of my lord, King Stephen and of mine, and also for the salvation of our sons, Eustace and William and of all our children”.

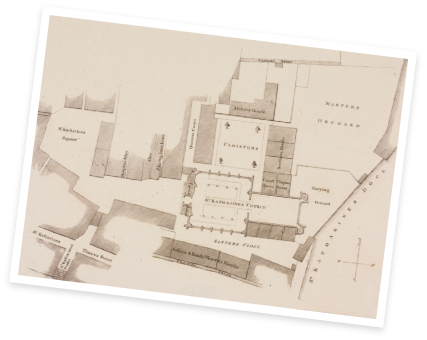

The duties of the Foundation lay in celebrating Mass, especially for the souls of those mentioned in the Charter, and in serving the poor infirm people in the Hospital. Matilda obtained a site on the east side of the Tower of London and the Church and Hospital were built there among open fields beside the river.

No plan of the original building has survived; but it was probably, like later buildings on the same site, on the usual plan of a medieval monastic hospital, with a large nave where the inmates were accommodated, cut off by a screen from the Chapel where services were held.

At an early stage the 13 poor persons were divided into a Master, or warden; 3 brethren, who were priests; 3 sisters, who were nuns; and 6 poor or infirm people who were looked after in the Hospital.

.png)

.png)